Blog Archives

What Does the Natural Self Look Like? The State of Not Losing the Soul Is Emotional Openness and Joy, Being Equally Free in Tears and Laughter

Integrated with The Way, One Becomes “Lighter” Through Life … Expansive Soul Energy Dances Through the Person: Return to Grace, Part Five — The Natural Self

Return to Grace

What can be the result of making these kinds of changes? Once again I look cross-culturally to give examples. But looking at the extraordinary childhoods of particular people provides contrast and insight also.

The Natural Self

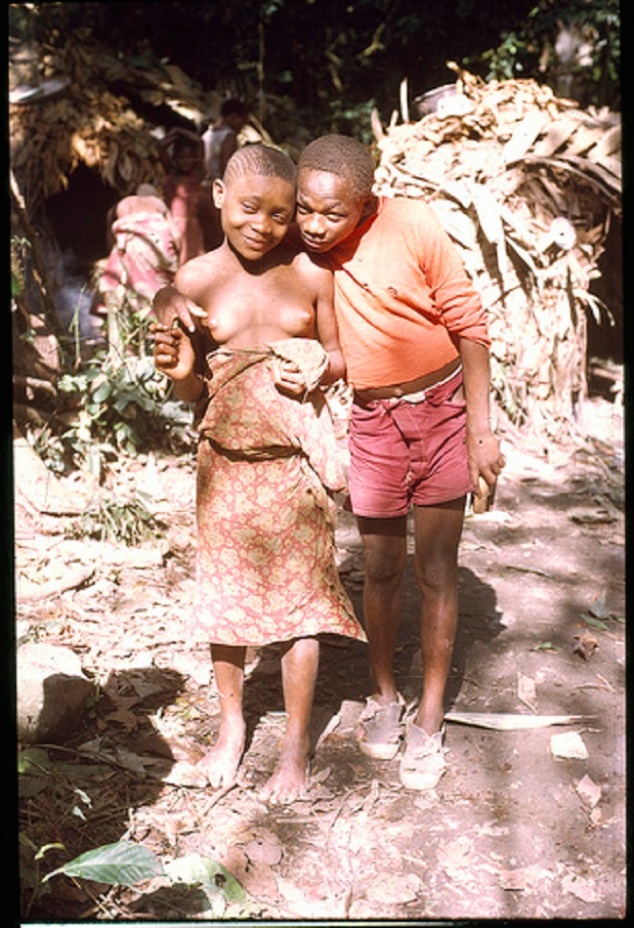

First, let us hear how Turnbull (1961) describes the results of the more trusting, more respectful childhood of the Mbuti. He describes the emotional openness and joy that characterizes the Pygmy adult:

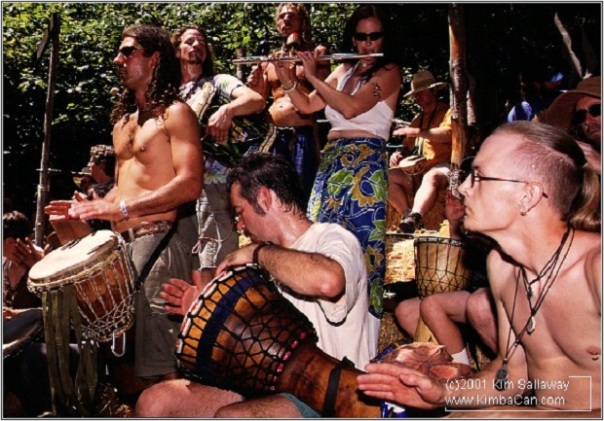

When Pygmies laugh it is hard not to be affected; they hold onto one another as if for support, slap their sides, snap their fingers, and go through all manner of physical contortions. If something strikes them as particularly funny they will even roll on the ground. . . . (p. 44)

They clapped one another on the back and held onto one another for support as they laughed, inventing all sorts of things they would do and say to any girl who answered them in such a way. The Pygmy is not in the least self-conscious about showing his emotions; he likes to laugh until tears come to his eyes and he is too weak to stand. He then sits down or lies on the ground and laughs still louder. (p. 56)

Equally Open to Grief and to Laughter

But this is not to mean that they do not feel sorrow. In fact, quite the opposite is the case. They seem to be equally as open to grief as to laughter, able to go into either deeply and fully. Considering all we are being taught by counseling psychologists on the need to fully have a period of grief when confronted by loss, it may be that we need to look to the Pygmy temperament as an example of that ideal. Turnbull (1961) relates,

But when someone really dies, for ever, there is among the Pygmies a burst of uncontrollable grief, not only from the relatives, but from friends. Even men will weep if they have been close to the dead person. It is a very different sound, and a terrible one. . . . (p. 42)

The Way

Raheem (1991) describes her understanding of the state of not losing the soul, which apparently happens in some unusual people.

On the other hand, the person who follows her own soul and uses the vehicle of personality to execute its purpose, will become “lighter” through life. There will be a sense of flowing easily from one moment to the next, as though she were in a beautifully choreographed dance which she had thoroughly mastered.

The free, expansive soul energy can dance through the whole person, bringing creativity, spontaneity and vitality throughout mind, body and emotions. And since such a person is on course, integrated with her own Tao, she can experience strength, tranquility and certainty from within herself. (p. 31)

Continue with Is the Supernatural Terrifying? The Idea of a Shamanistic, Stormy Spiritual Path Is Too at Odds with Our Religious Anti-Body Culture to Be Easily Accepted

Return to By Adolescence “Civilized” Children Are Programmed … Whereas in Primal Societies Inner Experience is Cultivated: Return to Grace, Part Four — Puberty, Becoming Adult

Notes

1. Related information about the Mbuti is brought out in this article by James R. Coffey. In The Mbuti of Central Africa: The Only Known Egalitarian Society (with Rare Video), he writes,

…the Mbuti have no rulers, no political structure, and except for a religion that essentially ties them functionally and ritually to the forest, they have no cohesive social structure. Most significantly, every man, woman, and child has equal access to resources–which is the very definition of egalitarian.

Men and women have equal power, decisions are made by group consensus, and minor disputes are usually dealt with by ridicule, gossip, or shunning….

…the fact that their social structure promotes gendered equality does not prevent individuals from attempting to promote hierarchy; they are simply ignored and considered insane.

…one point of particular distinction in Mbuti society is that children have what could be considered an irrational amount of power in ritual situations–believed to be most closely connected to the primal spirits of the forest.

…most Mbuti villages (which are usually comprised of only a few essential huts), are laid out to represent a human female womb in shape and design. This is so that when entering and exiting the village (and each hut), you are symbolically reborn–of your mother and of the forest.

…the village and physical use of space is thought of as male (in concept), while the exact layout, shape of the huts, and actual utilization of the space is thought of as female. Thus, it is a constant representation of sexual interaction, reflecting both human physical intercourse as well as symbolic birth by way of the forest….

2. Also see, on the site Peaceful Societies: Alternatives to Violence and War, the post titled “Encyclopedia of Selected Peaceful Societies: Mbuti.” Quoting from the article,

Beliefs that Foster Peacefulness. The Mbuti view their forest as a sacred, peaceful place to live—they constantly refer to it with not only reverence but adoration. They sing songs to it, in appreciation for the care and goodness they feel they get from it. If something goes wrong in their camp at night, such as an invasion of army ants, the problem is that the forest is sleeping, so they sing to awaken it. Their songs of rejoicing, devotion, and praise serve to make the forest happy. They do not believe in evil spirits or sorcery from the forest as the nearby villagers do–their forest world is kinder than that.

Avoiding and Resolving Conflict. Normally the Mbuti settle conflicts with quick actions. One of their major strategies is laughter, jokes, and ridicule. The camp clown, an individual who assumes the responsibility of trying to end conflicts through ridicule, uses mime and antics to re-focus the conflict on himself, to get everyone laughing and ridiculing, in order to divert attention from the issue of the moment. The Mbuti have no formal methods for resolving disputes or crimes, and no individual would pass a sentence on another. But if one person is clearly in the wrong, an entire camp can react by punishing, perhaps even thrashing, an offender. Sometimes parties to a dispute might settle it through arguments or mild fighting. Ostracism is always a possibility, but it is rare.

Gender Relations. Mbuti men who still live in the Ituri Forest organize and control the net hunting, though the women help them. The women gather vegetable foods in the forests, such as mushrooms (see photo), but the men will help out. The women freely join discussions with men, though tensions between the sexes do arise. One strategy they use to diffuse gender tensions is to have a “tug of war,” the men and boys opposite the women and girls. If the males begin to win, a man will leave his side and join the women, mockingly encouraging them in a falsetto voice. When that group begins to win, a woman drops off her side and joins the men, encouraging them in a deep bass voice to greater efforts. The fun and ridicule grow as the contest continues, until everyone dissolves into hysterical laughter. The effect is to ridicule aggression, competitiveness, and conflict itself. Both sexes will do whatever they can to survive and support their families in the refugee camps.

Raising Children. A Mbuti mother develops a special lullaby that she starts singing to her baby while the infant is still in the womb. She reassures the child about the world into which he or she will soon be born, with descriptions of the goodness of the forest and the supportiveness of the human environment. As they grow older, children learn to play non-competitive games that emphasize cooperative activities. Sometimes children are spanked and slapped by their parents….

Strategies for Avoiding Warfare and Violence. Different groups of Pygmies try to avoid warfare with one another. One incident that occurred during the honey-gathering season indicates this tendency. With everyone spread out through the forest in small groups to gather the honey, the Mbuti suddenly realized that a foreign Pygmy group had invaded their territory and were stealing honey from their trees. One man became excited and tried to summon everyone to make war on the invaders. But another man explained that they invade each other’s territories every year, and no harm is done as long as the different groups don’t encounter one another. If they do have a chance encounter, the invaders simply flee back to their own territory, leaving behind everything they have stolen.

3. In other places the Mbuti have been put forth as a possible model for exemplary parenting and care of children.

3. In other places the Mbuti have been put forth as a possible model for exemplary parenting and care of children.

4. Also see, on the site, Peaceful Societies: Alternatives to Violence and War, the post of May 9, 2013 titled “Mbuti Cherish the Forest—Does Anyone Care?” Quoting,

This 5:44 minute video, just released to Vimeo last week, was clearly prepared as a way of celebrating with viewers the traditional skills and lives of the Mbuti, and, just as importantly, of raising awareness about the stresses and traumas those people are enduring….

“Everyone is important in the hunt,” he tells us, with a fetching image of a Mbuti woman and a baby on her back on the screen. He describes how the hunters stretch their nets through the forest, and how the women and children make enough noise to drive animals into the nets for the men to kill. Then, he says, “we divide the meat into small pieces so that everyone in the group can have some.” Their forest tradition clearly includes fond memories of the custom of sharing.

Another man, identified as Chief Mangubo, takes over and tells us about the importance of the ancestors, and of music, to the Mbuti. The people play, dance, and sing every day as a way of communicating with their ancestors, he says. They welcome a new baby into the community through the performance of a special dance. They sing to insure the success of the honey collection season, they sing to celebrate marriages, to accompany their initiation rituals, and sometimes just to show their happiness. If problems come up, they hope their songs will elicit assistance from the ancestors….

…the closing credits indicate that armed guerillas attacked the Okapi Wildlife Reserve headquarters in June 2012 in retaliation for the efforts of the park guards to cut down on the poaching, which is decimating the wildlife. The fighters raped dozens of women, killed six people, and took over 50 hostages. They looted and burned the buildings. People that could, fled into the forest. The Mbuti featured in the video, people who lived near the park headquarters, have disappeared, and their whereabouts are still unknown.

Mbuti: Children of the Forest from JH Wildlife Film Festival on Vimeo.

Continue with Is the Supernatural Terrifying? The Idea of a Shamanistic, Stormy Spiritual Path Is Too at Odds with Our Religious Anti-Body Culture to Be Easily Accepted

Return to By Adolescence “Civilized” Children Are Programmed … Whereas in Primal Societies Inner Experience is Cultivated: Return to Grace, Part Four — Puberty, Becoming Adult

To Read the Entire Book … on-line, free at this time … of which this is an excerpt, Go to Falls from Grace

Invite you to join me on Twitter:

http://twitter.com/sillymickel

friend me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sillymickel

By Adolescence, “Civilized” Children Are Programmed … Whereas in Primal Societies Inner Experience is Cultivated: Return to Grace, Part Four — Puberty, Becoming Adult

“Civilization” Brings Brutal Rites of Passage and Fear of the Supernatural: The People of Nature Just Laugh at the Townsfolk Living in Such Terror and Valuing Cruelty

Finally, let us investigate the fourth fall from grace, the time around puberty when the ego is consolidated around a specific identity, task, role that marks her or him for life. Can this be otherwise?

Forest and Village Worldviews are Directly at Odds

Once again, Turnbull’s (1961) report on the Mbuti provides a fitting example. This example is especially illuminating in that he was able to observe and note differences between the hunter-gatherer Mbuti and nearby villagers with whom they had occasional contact. Since the villagers have to be considered post-agrarian and definitely not hunter-gatherers, we are able to study any differences between these two lifestyles and possible differences in worldview, side-by-side.

With “Civilization” Comes Brutal Rites of Adulthood and Excessive “Masculinity”

Indeed, Turnbull shows that these differences do exist, and we see one distinctly in connection to the rites of passage that are undergone respectively in each culture.

The rite of passage is called the nkumbi and is conducted by the villagers. The Pygmies undergo it, at a certain age, in order to enjoy certain respect and privileges in their dealings with villagers, as they must often have for various reasons. Of their own, the Mbuti have no such rite of passage, certainly nothing severe and harsh like that of the villagers. Turnbull (1961) describes the villagers’ nkumbi:

The physical ordeals sometimes start out as games but develop into cruel tests of physical endurance. A crouching dance that might be fun for a few minutes becomes agony after half an hour. A mild switching on the underside of the arm with light sticks is of no concern until, after several days, the skin becomes raw. And then the villagers notch the sticks so that they fold over and pinch the skin sharply, often drawing blood. When the boys have become used to being beaten with leafy branches, thorny bushes are substituted. (p. 225)

Dominant Societies Try to Instill Fear of the Supernatural to Control Their Underlings

He also explains the villagers beliefs concerning this rite of passage and its effect and purpose:

The villagers believed that the initiate, Pygmy or otherwise, is everlastingly bound thereafter by all the laws of the tribe, sacred and secular. He is put into direct relationship with the supernatural, whose representatives on earth are the villagers themselves. If any Pygmy initiate offends a villager, therefore, he is also offending the supernatural—the ancestors—and will be duly punished by them. The villagers live in such fear of the supernatural, with its power to bring down on an offender the curses of leprosy, yaws, dysentery and other diseases or to cause him to be injured by a falling tree, that they cannot conceive of any initiates daring to offend the ancestors. (p. 224)

But Primal Folks Laugh at the Fears of “Domesticated” Humans and Delight in Flaunting Their Customs

But offend the ancestors they do, these Pygmies, and with apparent relish. They do not share the villagers fearful view of the world. They cannot imagine any good reason to inflict these tortures on each other and laugh, secretly, behind the villagers’ backs, at them. Turnbull (1961) writes,

Both the boys and their fathers enjoyed the chance to make fun, in a friendly way, of the villagers, but that was not their sole reason for deliberately breaking all the taboos. They behaved as they did because to them the restrictions were not only meaningless but belonged to a hostile world. The villagers hoped that the nkumbi would place the Pygmies directly under the supernatural authority of the village tribal ancestors; the Pygmies naturally took good care that nothing of the sort should happen, proving it to themselves by this conscious flaunting of custom. (p. 224)

Building the Better Human – Entry Into Adulthood

To the Pygmies this all seems harsh and unnecessary, and as far as their own children are concerned they keep a strict watch over them to see that the villagers do not go to the length that they sometimes do with village children, even if this brings them into some contempt. But to the villager this toughening-up process is essential and does not come naturally in the course of village life. The child has to be fitted for adult life, and this is what the nkumbi sets out to achieve. In a few months a boy becomes a man, tough and strong, physically and mentally. The process is not a pleasant one, but it is the only way in which, under tribal conditions, the goal can be achieved.

The Pygmy can understand and appreciate this, but the very nature of his own nomadic hunting and gathering existence provides all the toughening up and education that are needed. Children begin climbing trees sometimes before they can walk. Their muscles develop, and they overcome fear in a number of daring tree games. Adult activities are learned from an early age by observation and imitation, for the Pygmies live an open life.

Their life is as open inside their tiny one-room leaf huts as it is in the middle of a forest clearing, and so the children have no need of the sex instruction which forms so large a part of the teaching given to village boys during the nkumbi. (pp. 225-226)

Far from illustrating the dependence of the Pygmies upon the villagers, the nkumbi illustrates better than anything else the complete opposition of the forest to the village. The Pygmies in the forest consciously and energetically reject all village values. When they are in the village they temporarily adopt its values and customs, not wanting to desecrate their sacred forest values by bringing them into the village. That is why they never sing their sacred songs in the village the way they do in the forest, and why they refuse to consecrate the nkumbi with special music, although every other event of importance in their lives is marked in this way. There is an unbridgeable gulf between the two worlds of the two peoples.

The Pygmies have their own way of growing naturally into adulthood. A boy proves himself capable of supporting a family when he kills his first real game, and proves himself a man when he participates in the elima. (p. 227)

By Adolescence in “Civilized” Societies Most Children Have Had the “Still Small Voice” Programmed Out, Whereas in Primal Cultures It is Valued

Aminah Raheem (1991) gives a final example of how this stage can be different in other cultures:

By the onset of adolescence, most children are intricately programmed into the cultural complex of their time and place. The “still small voice” of the soul is rarely heard and, when it is, it is usually discarded as fantasy or nonsense. For example, when I worked with late adolescents, I found that they often received deep soul promptings through dreams of visionary experiences. These numinous events seemed to contain valuable guidance for direction in their lives, but usually they were discounted by the dreamers and their peers as fantasy. By contrast, in American Indian culture such experiences are valued as clear messages of life purpose, especially when they appear during puberty. (p. 29)

Continue with What Does the Natural Self Look Like? The State of Not Losing the Soul Is Emotional Openness and Joy, Being Equally Free in Tears and Laughter

Return to Return to Grace, Part Three — The Primal Scene and the Divine Child: Hierarchical Societies Demand Conformity All the Way Down the Line

People of Programming … “Civilized” Ways

People of Nature … “Primal” Ways

Primal Ways and “Civilized” Ways Colliding Create Culture Wars

Primal Ways and “Civilized” Ways Colliding Create Culture Wars

Continue with What Does the Natural Self Look Like? The State of Not Losing the Soul Is Emotional Openness and Joy, Being Equally Free in Tears and Laughter

Return to Return to Grace, Part Three — The Primal Scene and the Divine Child: Hierarchical Societies Demand Conformity All the Way Down the Line

To Read the Entire Book … on-line, free at this time … of which this is an excerpt, Go to Falls from Grace

Invite you to join me on Twitter:

http://twitter.com/sillymickel

friend me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sillymickel

For, not only would these dominating and subservient traits be passed along to your children through heredity, but also through nurture and example. Your children could not help but be lured from their pulls toward natural ways, which they, by Nature, experience more strongly as they are younger and more recently removed from Divinity.

For, not only would these dominating and subservient traits be passed along to your children through heredity, but also through nurture and example. Your children could not help but be lured from their pulls toward natural ways, which they, by Nature, experience more strongly as they are younger and more recently removed from Divinity.  Your offspring with such traits would end up being great in number and your population would increasingly see and produce such inauthentic, more twisted humans.

Your offspring with such traits would end up being great in number and your population would increasingly see and produce such inauthentic, more twisted humans.